Work in progress: “My Mary Magdalene” series, Sherry Wiggins and Luís Filipe Branco, 2024.

I have been in Portugal for a week and a half, settling into the Cortiço Artist Residency and thinking about Mary Magdalene. I have started working with my creative partner, Luís Branco, on my embodiments and performative photographic work with Mary Magdalene. It takes some time, this process with my heroines—my research has gone on for several months. And now, the enactments/embodiments with Luís are coming forth. We have set up a photo studio and shot many images of this wondrous heroine this week. The image above is one of the best from this week. There will be more …

“Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy,” Artemisia Gentileschi, 1620-1625. private collection.

The painting above is by Artemisia Gentileschi and is one my favorite images of Mary Magdalene.

I have been studying images and ideas of Mary Magdalene, as represented by artists, scholars, feminists, and popes. I have looked at many paintings and images of her, and I have engaged with narratives in the New Testament and in the Gnostic gospels. I have explored the Gospel of Mary, an extracanonical text from the second century CE that was found in a cave in Egypt in the last 150 years. This is the only gospel named after a woman, and it is named for Mary Magdalene. It is a stunning depiction and explanation of the spiritual understanding of Mary Magdalene in relationship to her teacher, Jesus. I am a neophyte when it comes to the subject of Christianity, so forgive my ignorance; I have delved into this subject from Mary Magdalene’s point of view. I realize I am traversing sacred and complicated ground here. Mary Magdalene, as a figure and a metaphor, is a huge subject, considering the history, the mythology and the misogyny that surround her. She is my most complex heroine to date.

Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1656) is known for inserting her own image into paintings of her heroines, many of them biblical figures. She made several paintings of the Magdalene. In Gentileschi’s painting above, MM is depicted in a state of spiritual and physical rapture. Can we have both at the same time? This is the paradox and the beauty of the idea of Mary Magdalene. Her body is our body—her neck, her hair, her spirit. (Though in Western art she is almost always depicted as a beautiful, young, white woman). Portrayals of her are contradictory: a saint cloaked in red, a bare-breasted penitent, a contemplative beauty, an ascetic covered in hair and carried by angels. She has been revered and scandalized and depicted in multiple incarnations throughout time.

“Baptistry wall painting: Procession of Women,” 240-45 CE, Dura-Europos, Yale University Art Gallery.

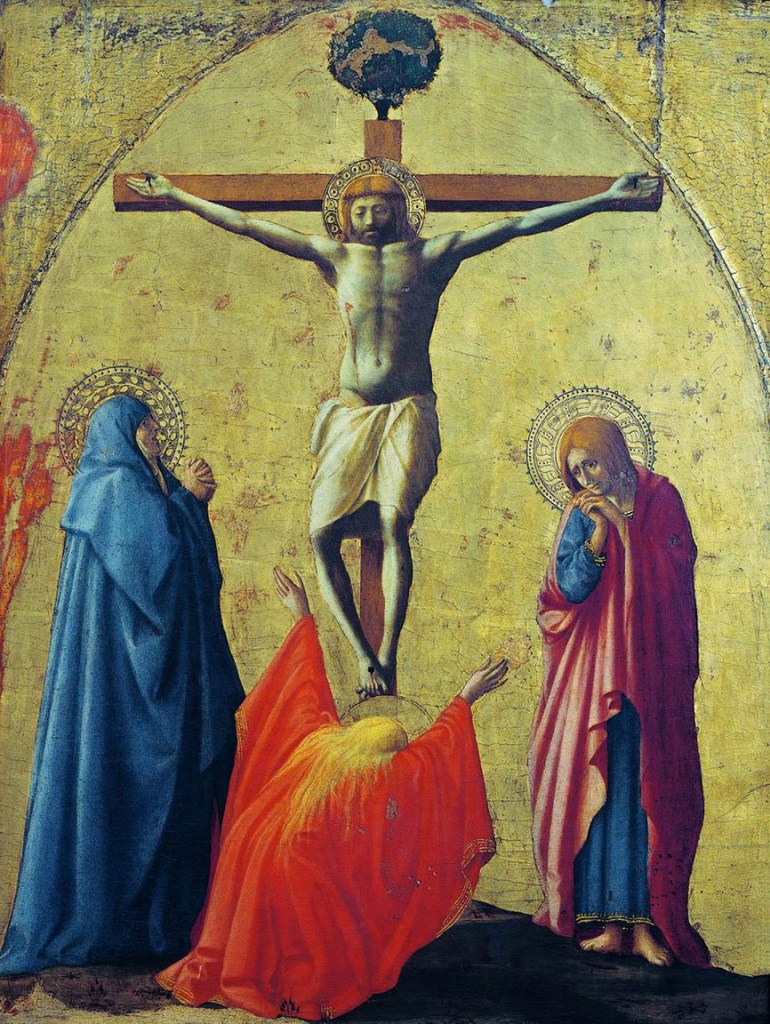

Above is one of the first known depictions of Mary Magdalene, found in one of the world’s earliest house-churches in Dura-Europos in modern-day Syria. We (secular historians, biblical scholars and the rest of us) don’t know much about Mary Magdalene nor much about the early history of Christianity or Jesus. There is no written history from the early days. Biblical scholars and historians think MM was a real historical figure (as was Jesus) living in Galilee in ancient Judea in the first part of the millennium, when Judea was under Roman occupation. The New Testament gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—mention Mary Magdalene more than any of the other women who followed and surrounded Jesus. She is said to have been present at Jesus’s crucifixion (notice her in red in Masaccio’s painting below with the Virgin Mary on the right and St. John on the left). Magdalene is said to have witnessed his burial and was perhaps one of the first to have witnessed his resurrection. The canonical gospels were probably written in the first hundred years after Christ’s death and were most likely rewritten again and again, so their historical accuracy has been disputed over the centuries.

“Crucifixion,” Masaccio, 1426, Capodimonte Museum.

We don’t really know what the name Mary Magdalene signifies. There were many Marys (Miriam in ancient Hebrew) surrounding Jesus in the gospels and in real life during this period. The term “magdala” means tower; it was also the name of a fishing village located on the west side of the Sea of Galilee, where Jesus was teaching. Mary Magdalene was not associated with any man—neither a father nor a husband (which almost all women were in the patriarchal society of the time). One of the gospels tell us that Jesus cast “seven demons” out of her. Jesus was known as a healer, an exorcist of sorts. This idea of MM’s “demons” has been used over time to portray her as a former prostitute or adulterous woman. However, these kinds of healings were supposedly practiced by Jesus as a form of psychological and physical healing. It is said that Mary Magdalene became a hands-on healer herself as one of Jesus’s disciples. Magdalene was most often pictured with an unguent bottle or jar, representing the oil and herbs used for many things, including healing and caring for the body after death. Mary and the other women who accompanied her to Jesus’s tomb after his burial sought to anoint him with these special herbs and unguents.

“Mary Magdalene as Melancholy,” Artemisia Gentileschi, 1622 -1625, Museo Soumaya, Mexico City.

Above is another painting of Mary Magdalene by Artemisia Gentileschi. It serves as a symbol of melancholy. What was Mary Magdalene healed from? Artemisia (and I) can relate to this feminine/feminist “melancholy” and the expelling of it. In this painting, a downcast Mary Magdalene is draped in loose, beautiful fabrics; her soft, gold-tinged hair (it is always about the hair with MM) falls over her shoulder and winds around her fingers. In the gospels, MM and other women disciples or followers of Jesus, are described as “out of their resources,” implying that these women were in possession of wealth that they shared with Jesus and his followers. MM is often portrayed (especially in the Renaissance and Baroque periods) in beautiful garments with a mirror, a skull and a candle, representing the shedding of vanity, acknowledgement of the transitoriness of life, and the search for spiritual awakening. French Baroque painter George de La Tour (1593 – 1692) painted several series of the Magdalene in deep contemplation with a mirror, a skull and a candle. I particularly love the painting below, which Luís and I have used as an entryway to our work with Mary Magdalene. You can see our interpretation of George de La Tour’s painting below. The first image on the blog has some of the melancholy expressed in Gentilieschi’s painting.

“The Penitent Magdalene,” George de La Tour, 1640, The Met collection.

Work in progress: “My Mary Magdalene” series, Sherry Wiggins and Luís Filipe Branco, 2024.

What happened to Mary Magdalene after Jesus’s crucifixion (and resurrection) is unclear. She was called “the apostle to the apostles,” which means that she was charged with spreading the “word” of Jesus, as were the other apostles (there were no written texts by Jesus). This might also signify that MM had experienced and understood some deeper teachings from Jesus. The term “apostle” means disciple and follower; it also signifies a duty as an evangelist or proselytizer to spread the word. Many stories detail the Magdalene leaving Judea and going to Ephesus, to Rome, and to France (there is a very detailed story/myth (held deeply by many) about MM going to France). She performed miracles, taught and later lived in a cave and meditated for many years. Her “relics” are worshipped all over the Mediterranean and beyond. She is worshipped and sanctified in many Eastern and Western Christian traditions. Perhaps she did get in a boat and teach and practice after Jesus’s death. Most secular historians hypothesize that she stayed in Galilee, where she taught and preached. These early years were dangerous times for Christians, and I imagine they were even more dangerous for a female spiritual teacher.

The erroneous or unfounded idea that Mary Magdalene was a reformed prostitute or an adulterous woman before meeting and being healed by Jesus was introduced into church doctrine in 591 by Pope Gregory. He conflated many of the women named Mary and unnamed women from the gospels. This idea held for hundreds of years, and Mary Magdalene became a figure and a symbol of penitence from then onward to saintliness.

Innumerable paintings of the repentant Magdalene emerge during the Renaissance, and usually involve her boobs as well as lots of hair. She is often cast in nature, or in the mythical cave that she was said to dwell in in France, according to one of the many stories/inventions of MM. The Italian Renaissance painter Titian (1488 – 1576) created several paintings of the penitent Magdalene during his lifetime, the first one, in 1531, with a lot of hair barely covering her breasts. The last one, in 1560, included less hair and partially covered breasts. An unguent bottle appears in the lower left corner of both paintings. The skull appears only in the later painting.

“Penitent Magdalene,” Titian, 1531. Palazzo Pitti collection, Firenze.

“Penitent Magdalene,” Titian, 1560. Hermitage Museum collection, St. Petersburg.

The Renaissance produced many images of Mary Magdalene with her breasts revealed (got to love the Renaissance). The painting below verges on campy porn. It was perhaps painted by Giampietrino (1495 – 1549), who was a student of Leonardo da Vinci’s, though some think this painting is by Leonardo himself.

“Mary Magdalene,” Giampietrino, 1515, private collection.

And I love the image below by French Baroque artist Simon Vouet (1590 – 1659) of Mary Magdalene carried by angels.

“Mary Magdalene Carried by Angels,” Simon Vouet, Musée des Beaux Arts, Besancon France.

I am not clear on when Mary Magdalene was declared a saint (or how this works ?). During the medieval period she was a big deal and her iconic images from this time are many and beautiful. We also see the “hairy Mary” images, where Mary Magdalene is conflated with the “Mary from Egypt” who was also a supposed repentant sinner who went into the desert and lived in a hair garment or a coat of her own hair. Notice the bottle of unguent in the images, the halo, the hair coat, the life stories of Mary Magdalene, Donatello’s magnificent wooden sculpture and finally Lady Gaga as Mary Magdalene. So many Marys …

“Saint Mary Magdalene,” Paolo Veneziano, c. 1325 – 30.

“Maddalena penitente e otto storie della sua vita, Maestro della Maddalena, c. 1280 – 85, Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze.

Penitent Magdalene,” Donatello, c. 1440, Museo dell Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

“Lady Gaga’s Mary Magdalene,” I am not sure where I found this image, but I love it.

A few of my recommended sources:

“Mary Magdalene: A Visual History,” Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane, 2023, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

“Mary Magdalene: Truth and Myth,” Haskins, Susan, (new edition 2007), Random House, UK.

I will be working over the next two and a half weeks in Portugal on both my heroines Mary Magdalene and the goddess Circe with photographer Luís Branco. I wrote about Circe on my previous blog post.