The Mirror of Helen, 20 x 30,” 2022

This conversation with curator and writer Cydney Payton took place in relationship to the exhibit On Sappho, Helen and Aphrodite, an exhibition of performative photographs I produced in collaboration with photographer Luís Filipe Branco. The exhibit will be on view at Michael Warren Contemporary in Denver, Colorado October 31st to December 2nd 2023. The opening reception is November 2nd from 5 to 8pm and an artist talk will take place November 18th from 10:30 to noon.

CP: Congratulations on your show, On Sappho, Helen and Aphrodite, at Michael Warren Contemporary.

SW: Thank you. I’m excited to talk with you about it!

CP: To frame our conversation, you have been engaging with other artists’ images and practices as a modality of self-exploration for more than a decade. You referred to your practice as performative but also as embodying and enacting.

SW: I am compelled to study the lives and work of women. In doing so, I have found a kind of courage and sense of self-power. That has led me to create an artistic practice that is more performance based.

The women I study become the subjects of various projects and bodies of work. The photographs document my artistic process and the practice itself; the photographs are also the intended result. While I am performing, I envision the poses to be a photographic work. Yes, enactment and embodiment—the terms you mention—are definitely the terms that describe this work.

The beauty of performative art for me has been that my body can exist in different environments. Somehow those environments—sites, places, atmospheres—come to represent the women I am thinking about and making work about. That process is empathic, yet it exists because I have excavated and studied their lives and work. Until recently, most of those women were artists. Now, I am working with a broader representation of historical and feminine voices in creating the Heroines Project.

CP: You are very process driven in your artistic practice. You make a lot of images.

SW: The work is created through in-depth research, editing, and post-production of thousands of images. Each image goes through the processes of the performative act, lens and shutter, preproduction on a digital screen/film, printing, and, finally, exhibited object.

But in the end, I am forever an installation artist. Thus, the final narrative of an exhibition arrives because I care about the spatial dynamics between the audience and the art. An exhibition offers a liminal plane where the viewer and the object—the concept and the artist—participate. In the case of On Sappho, Helen and Aphrodite, I hope to create a way of confronting volumes of history largely written by men.

Sappho’s Crown, 22 x 33,” 2022

CP: The exhibition insists upon directness of viewership. We cannot look away. We are obligated to make comparisons, historical and contemporary, among these three iconic representations of the feminine. Sappho is the first heroine you bring into view. Her words, from the few remaining papyrus fragments, are sprinkled throughout the installation in excerpts taken from translations by Diane Raynor and poet Anne Carson. These traces of Sappho, which have survived over centuries, to be investigated, translated, and (re)interpreted, anchor the show.

SW: I investigate women, both fictional and real, such as Sappho. She was a real person; we know that because we have her words. Helen and Aphrodite are mythical and archetypal figures, but for me Sappho has an artist’s voice. As I delved into the translations of her texts, which were originally songs meant to be performed and sung and accompanied by dancers and instrumentation, I found her to be so modern. And her subjectivity feminist and feminine. She is speaking from 2,800 years ago, and, even so, the work resonates with me as being in the present moment.

In Poem #58, which is also called “The Old Age Poem,” Sappho speaks to me as an artist very directly, as she speaks about herself at an older age. In truth, I am inserting myself into the lives and stories of these heroines from my position as a sixty-something-year-old woman.

CP: Even though your photographs present a type of romanticism in tone and composition, there is a feminist message about love in the work that pervades the exhibition.

SW: Love means many things. Gender might be implicit, but it is also fluid. Though Aphrodite was not seen as a supporter of lesbianism in the ancient Greek world, maybe because it’s mostly stuff written by men, she should be seen as totally supportive of all forms of love (and sexuality, too). I love this line that Aphrodite speaks to Sappho: “Who, O Sappho, is wronging you? For if she flees, soon she will pursue. If she refuses gifts, rather will she give them. If she does not love, soon she will love, even unwillingly.”

CP: Beautiful.

SW: There is this complexity of love, the giving and receiving, the joy and the loss, in the poem. I just love this advice from Aphrodite. And Sappho loves Aphrodite—she’s her main goddess, and she speaks with her a lot.

Aphrodite with Roses I, 30 x 20,” 2022

CP: The photographs also contain an abundance of symbolism, for example roses in the images of Aphrodite. For Aphrodite, you looked to the Pre-Raphaelite painting Venus Verticordia by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The painting is of a beautiful young woman with an apple and a dart. In your diptych, Aphrodite with Roses, you present us with an apple and a bouquet of red roses against a figure on a proverbial bed of roses.

Venus Verticordia, 32 x 26,” Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1864

SW: I was riffing on Venus Verticordia. I don’t expect the viewer to make that connection, but roses do serve as a backdrop in both the painting and in the diptych. The roses are brought forward to perhaps deliver other meanings. Both Venus and Aphrodite are usually represented as beautiful and sometimes sexy young maidens. Rossetti’s painting sort of morphed into the work in the moments when photographer Luís Branco and I were making these pictures. I had an idea of where I wanted to go. We set up the photo shoot toward that idea. Even so, every photograph has its own performative life, such as it did with creating Aphrodite. The image is obviously me, an older woman, and you see all the wrinkles on my neck and face.

Aphrodite with Roses II, 30 x 20,” 2022

CP: Your decolletage.

SW: My decolletage. And my breast is exposed, as Venus’s is in the painting. The work is compressed and cropped, cut off, and presented larger-than-life size. The face and the boob and the arms, the roses, everything operates against a natural sense of scale.

CP: Rossetti’s version was also the first time that he painted a nude figure. He, too, compressed and zoomed in to create an artificial reality that reads more intimate and sexualized. His other images were more full-bodied and fully clothed. There is a mirror between your image and Rossetti’s image as far as being on the heterosexual edge of desirability; it’s almost camp.

SW: After making and producing these photographs, I looked up who Venus Verticordia was in Roman mythology. I discovered that she was a goddess who protected young women and older matrons from their own sexual appetites. This is the opposite of what my Aphrodite and the Greek Aphrodite are all about. I am inserting myself into Rossetti’s view but as this older woman who is sexualized through my autonomy of choice. I’m in a bed of roses as an older woman, not as a subject posed against roses to suggest a social norm of idealized beauty. My Aphrodite is one of generosity. She is for ALL love.

CP: Is Aphrodite your main goddess?

SW: I’ve always thought it was Aphrodite. As I learn more and more about her, I do adore her. But she is kind of tricky too. She actually put Helen in a bad position. It was Aphrodite who made a promise to Paris. In the Judgment of Paris Aphrodite tells Paris that if he gives her the golden apple and deems her the most beautiful goddess over Hera and Athena, she will give him the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. That was a little presumptuous, her doing that to Helen!

CP: Venus Verticordia also means “changes of the heart.” That could be one way of looking at Helen After Troy. The image presents us with a Helen full of regret, after the war, abduction, kidnapping (or elopement) with Paris. We all know about Helen from history, certainly the Odyssey and the Iliad, but you have augmented that reading with something new.

Helen After Troy, 33 x 22,” 2022

SW: We shot that photograph in March. We were shooting Helen with her gown and crown and jewels in the swimming pool. When I got out of the pool, it was dark and I was cold. We can see how miserable I was. That’s when Luís said, “Just one more shot.” I was like, “You know, Luís, I am fucking cold.”

Later, when I saw the proofs for the image, I thought, well here’s Helen after Troy. In the ancient story, Helen comes home from Troy with her husband, King Menelaus of Sparta. After the fall of Troy, he had been meaning to kill her when he captured her, but he couldn’t because she was so beautiful (and her breasts!). According to the Odyssey, he brings her home and they have a nice life in the palace in Sparta, entertaining guests with lavish parties.

And, who really believes that? How could she have gone through the torture of the ten-year war in Troy with thousands of Greeks and Trojans dying, purportedly because of her, and just go home and have a nice life in the palace? I thought this is what she really would have looked like. She would look like a drowned rat, a drowned queen. Helen After Troy is one of my favorite images in the show.

CP: Helen After Troy brings us to an alternative ending of what has been known. You point us there through the meta structure of your work. For example, Sappho’s poems reference both Aphrodite and Helen. And, when we take in the larger view, we can see you enacting Sappho, Helen, and Aphrodite in the context of the twentieth-century artist/performer Claude Cahun. How has Claude Cahun influenced this body of work?

SW: As you know, from the artist’s book THE UNKNOWN HEROINE that you and I worked on, Claude Cahun is the artist who has been influencing my work for a while now. Cahun was incredibly well educated. Her grandmother taught her ancient Greek, so she understood the breadth of history and classical literature. She was both a performance artist and an imagemaker who used herself in her photographs. Helen and Sappho came to me originally from Cahun, from her Heroines text, where she writes about fifteen women, mythical, real and fictional. She portrays Sappho in her short essay, written to be performed as a monologue, as Sappho the Misunderstood. And Helen is Helen the Rebel.

CP: Your photograph Sappho the Misunderstood is a parallel of Helen After Troy. Both figures step out of the darkness; neither is idealized. Even with the theatrical lighting, we can penetrate the deeper questions about Helen and Sappho. With Sappho, we sense all that ambiguity around her identity and life.

SW: Sappho is misunderstood on all these levels—her sexual preferences, whether she loves men, whether she loves women, whether she loves both. These are things that have been discussed throughout the ages. And then all the mythology of her jumping off the Leucadian cliff. Sapphic lore tells us that later in life, she was in love with Phaon, a young ferryman, who ditched her for a younger woman. Supposedly, she was so upset she jumped off the Leucadian cliff.

CP: You disagree with this?

SW: Sappho would not be undone by Phaon’s betrayal. She was way too conversant with the fickle ways of love.

Sappho the Misunderstood, 33 x 22,” 2022

CP: The photograph suggests a defiance, as if she’s looking back at us across the ages. It is a tantalizing expression of a mystery that will never be solved.

SW: Yeah, I like that image a lot, too.

CP: Maybe this is the moment to ask: How does your feminist perspective inform your collaboration with Luís Branco as far as process and vision?

SW: When Luís and I work together, it’s like making a film. Beforehand, part of the research might be reading Sappho’s work, reading what historians and critics have thought about Sappho’s work, and studying paintings that have been made of Sappho through the ages. I also bring props, makeup, and outfits. We find sites, sometimes we create a staged setting. For Sappho, Helen and Aphrodite we worked outdoors in different locations in Holland and in Portugal.

It takes me a while to get into character. Part of the process becomes interacting in different spaces at different times—early morning, day, and night. What happens emerges from the connection to the site, the materials, the research, and the collaboration. In the process I do not camouflage my sixty-something-year-old persona. I attempt to embody these female icons from the truth of my body. Luís is very good at pushing me into character. We do literally take hundreds and hundreds of images to find those that are just right.

CP: There are many artists who are working with identity, such as Cindy Sherman, who take their own pictures. You know how to take pictures. What does Luís’s perspective bring to the work that you couldn’t do on your own?

SW: Our interaction, the collaboration, we call it a push-pull. He is, in essence, the viewer. People have asked why I don’t work with a female photographer. The fact that he is a man creates a kind of friction. Sometimes friction, sometimes seduction, that goes back and forth. For example, with the making of Helen After Troy, he saw what was possible.

CP: He brings an objectivity to the moment that you could not.

You describe it as cinematic or filmic, which sits within the language of moviemaking. Is that a more important language for you now than the language of performance? Have you crossed over from thinking about visual art into thinking more about the cinematic nature of visual art?

SW: I’m not trained as a performer—that’s something that’s just happened through this process, happened more and more. Taking on these big-time heroines, I must rise to be Aphrodite, to be Helen of Troy. I would say, there is this cinematic quality to the images because they are photographs. On Instagram these images operate in the public melee of social media. But when I exhibit them in a gallery, the physicality of the images allows people to really respond. The response is not just older women saying, “Wow, this is really cool!” Younger women, older men, queer people, respond. Everybody has a mother or a sister or a lover or whatever. I’m your everyday girl, but …

CP: There is a kind of surrogacy in the visual plane that you can step into.

SW: People see me not just as Helen but as me, the sixty-eight-year-old artist-performer woman who is not afraid to be seen.

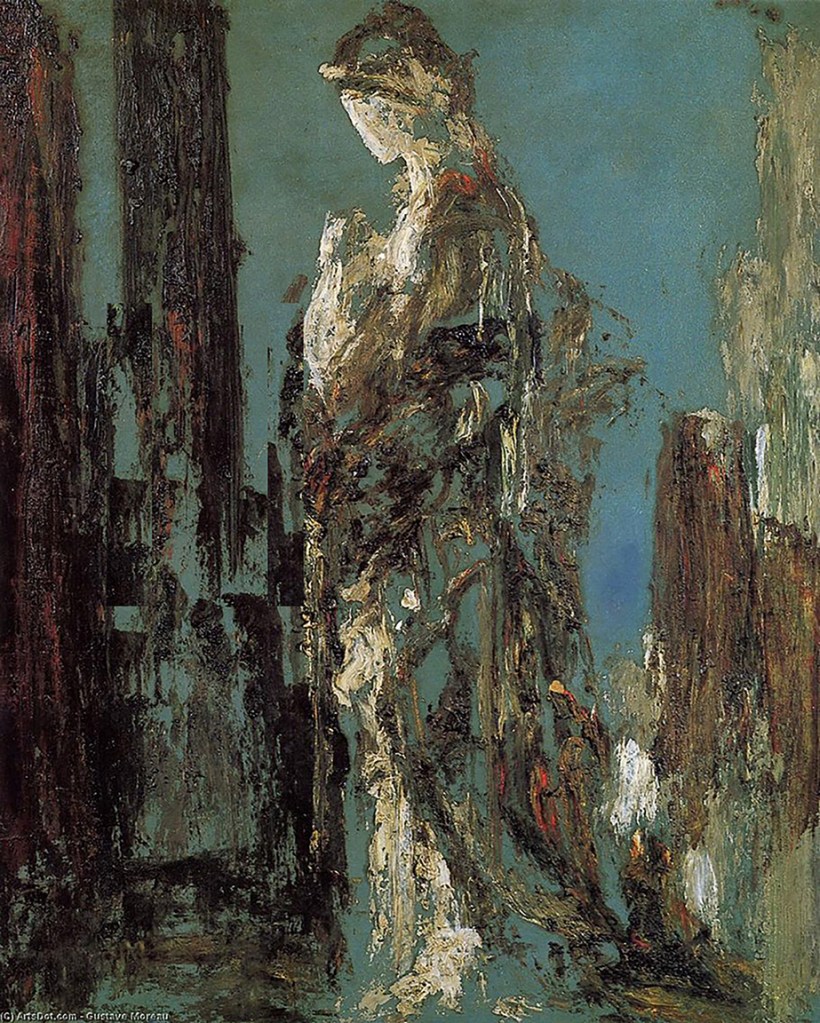

Helen’s Eidolon, 30 x 20,” 2022

The exhibit On Sappho, Helen and Aphrodite will be on view October 31st to December 2nd 2023 at Michael Warren Contemporary in Denver, Colorado. https://www.michaelwarrencontemporary.com/

The opening reception is Thursday November 2nd from 5 to 8pm and the artist talk will be Saturday November 18th from 10:30am to noon. There is a concurrent exhibition of Ann Marie Auricchio’s work. Gallery hours are Tuesday to Saturday 11am to 5pm.