“Circe,” Franz Stuck, oil on wood, 1913, Alt Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

The painting above pictures the Greek goddess Circe, who we know from Homer’s The Odyssey and other texts, as a mesmerizing temptress offering a golden goblet of her drugged wine (which purportedly turns men to pigs). In March, I will be embodying the ancient Greek goddess Circe, my most recent heroine, in performative photographs with my collaborator Luís Branco. And so, I am contemplating (obsessing over) the enchantress and how she has been portrayed throughout the ages.

“Circe and Ulysses,” Francesco Maffei, oil on canvas, c. 1650, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.

In my circuitous investigations into Circe I stumbled upon this painting of Circe and Ulysses / Odysseus by Italian baroque painter Francesco Maffei. Here is the whole thing: Circe meets Odysseus and sparks fly. Maffei’s painting is a hallucinatory revelation; the figures are distorted; we can’t really discern what’s happening. We know that Circe offers Odysseus the drugged wine that has the power to change humans into wild animals. However, it’s as if the figures of Circe and Odysseus are merging, their bodily boundaries melding. The mercurial god Hermes (shown in the background) has warned Odysseus and offered him an antidote to Circe’s potion. To Circe’s surprise, her spell is thwarted. What might have been a zone of terrifying transformation for Odysseus transforms into the best foreplay ever. Circe has met her match in trickery and falls in love.

Who is this goddess who alters men? How is it that she has captured the imagination of singers, writers, and artists throughout the ages? How do Circe and Odysseus solve the puzzle of loving and letting go?

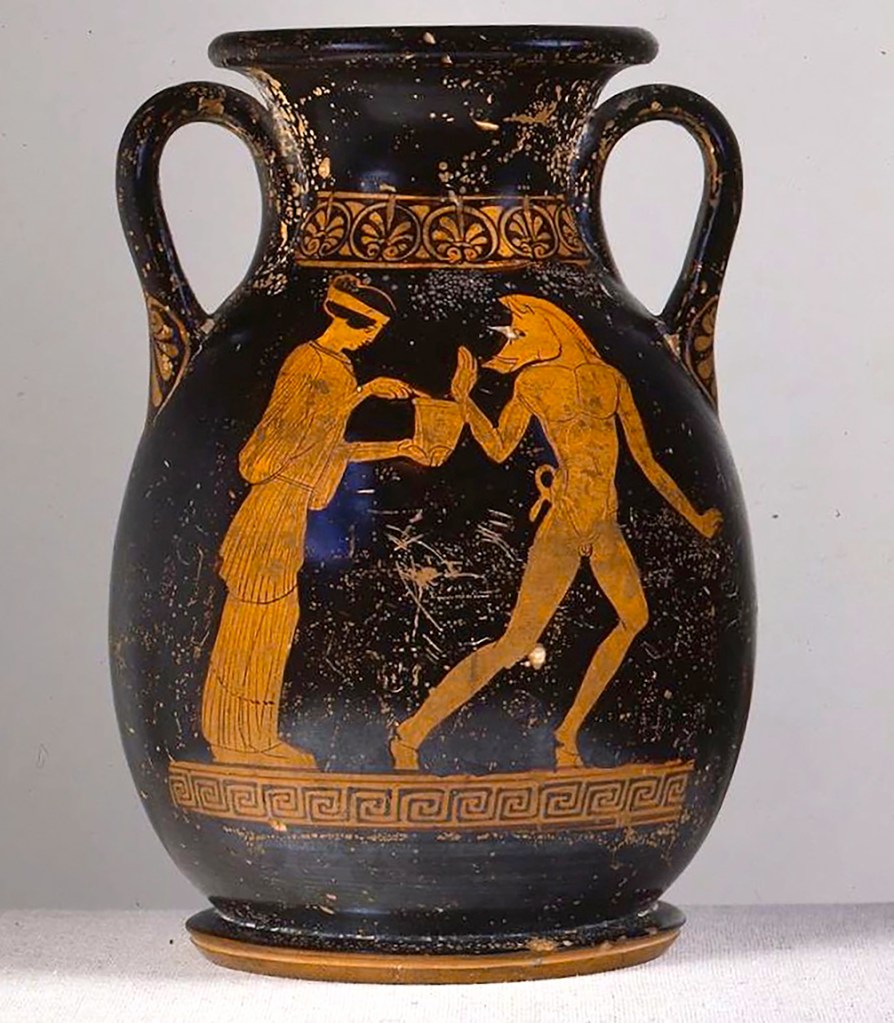

The goddess Circe and one of Odysseus’ half-way transformed men, Athenian pelike, c. 5th century BCE, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

.

The ancient Greek vase above depicts the well-known scene from Homer’s The Odyssey, where Circe transform half of Odysseus’ men into pigs. Like Odysseus and his men, I have fallen under Circe’s spell, as I have been searching for her and researching her.

Circe first emerges (in written words that we know of) in Homer’s The Odyssey, which was compiled around 800 BCE. Homer’s Circe was more than likely a compilation of other ancient primordial goddesses of the near and far east; it is fascinating to examine the associations of Circe with earlier matriarchal goddess figures and their iconography, particularly in relationship with the animal world. First, her name, Circe, or Kirke in ancient Greek, is the feminine form of Kirkos, which means falcon or hawk.

According to Judith Yarnell:

Long before Homer imagined Circe, birds have been associated with the divine. According to Marija Gimbutas, birds appear in the prehistoric art of Europe and Asia Minor as the “main epiphany of the Goddess as Giver-of-all, including life and death, happiness and wealth.”

– from Transformations of Circe, Judith Yarnell

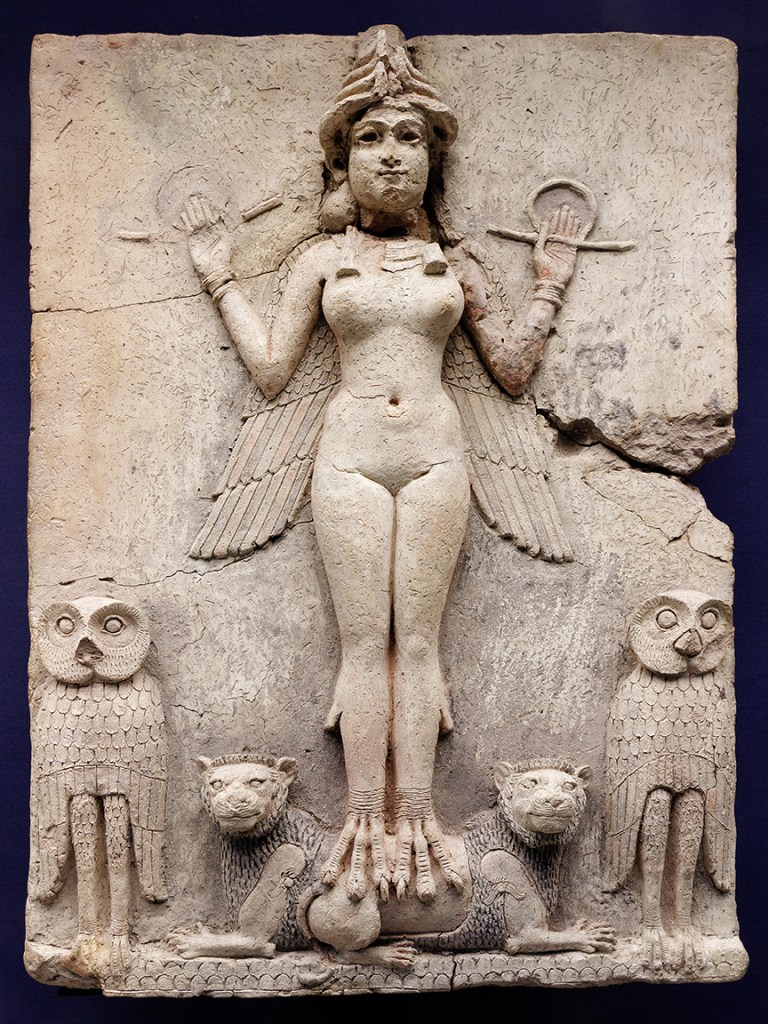

The Burney Relief, sometimes called Queen of the Night, c. 19th – 18th century BCE, Babylonia.

The ancient sculpture above, known as the Burney Relief, shows a beautiful, winged goddess (possibly representing the Mesopotamian goddesses Ishtar or Ereshkigal) with her taloned feet resting upon two small lions and flanked by larger owls. Perhaps this goddess prefigures Circe, as perhaps does Isis, the winged goddess of ancient Egypt, who is also associated with a bird of prey, the kite. Circe is not depicted with wings, but her connection to the animal world is apparent across time. Many stories and images exist that depict her wolves and lions, tamed companions, as well as other tamed (and sometimes drugged) wild creatures. Circe’s power to transform human beings into swine and other animals is another major aspect of her mythos.

Kylix (wine cup) depicting Circe giving an antidote to Odysseus’ men, Greek, Archaic Period, c. 560 – 550 BCE.

The sixteenth-century fresco below, by Allesandro Allori, illustrates a part of the Circe story found in The Odyssey and subsequent texts. The goddess is seated on a rocky bench in the foreground, looking contemplative and a little melancholic. She rests her face in the palm of her hand, her book of spells at her side. She calmly points her magic wand toward a wolf and a lion, both seated before her. A second lion peers out from beneath Circe’s bench. Both lions gaze outward, appearing almost human. In the middle ground, the naked god Hermes (identified by his winged helmet) offers Odysseus the special herb that will protect him from Circe’s spells. Odysseus’ men move chaotically in the background, presumably fearing the goddess’s special powers. Their ship rests moored in the pale distance.

“Circe and Odysseus,” Allesandro Alloriand collaborators, fresco, c. 1575 – 1576, Palazzo Salviati, Florence.

I have been reading Emily Wilson’s 2018 translation of The Odyssey. Wilson is the first woman to translate Homer’s epic into English. Circe emerges in Book 10 as a key figure in Odysseus’ long, perilous journey home to Ithaca following the Trojan war. Homer portrays Circe as a powerful and resourceful goddess, and I find her relationship with Odysseus strangely modern, verging on feminist, especially for a three-thousand-year-old text.

Below, I present images and paintings that best evoke Circe’s story along with quotations from Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey.

In Book 10: The Winds and the Witch, Odysseus recounts how he and his men first arrive at Circe’s island:

We reached Aeaea,

home of the beautiful, dreadful goddess Circe,

who speaks in human languages—the sister

of Aeetes whose mind is set on ruin.

Those two are children of the Sun who shines

on mortals, and of Perse, child of Ocean.

(10.135–140)

Odysseus and his men arrive at Aeaea exhausted and in despair (after their many misadventures). At first, they are unaware that they have landed on Circe’s island. They spend a couple of days recuperating on the shore. Odysseus, when exploring the island on his own, sees smoke rising from the forest above. After drawing lots, he sends half of the crew off to explore the island, and he stays with the other men near their ship. The men soon discover Circe’s house:

Inside the glade they found the house of Circe

built out of polished stones, on high foundations.

Round it were mountain wolves and lions, which

she tamed with drugs. They did not rush on them,

but gathered around them in a friendly way,

their long tails wagging, as dogs nuzzle round

their master when he comes back home from dinner

with treats for them. Just so those sharp-clawed wolves

and lions, mighty beasts, came snuggling up.

The men were terrified.

(10.210–219)

“Circe,” Wright Barker, oil painting, c. 1889, Bradford Museums and Galleries, West Yorkshire.

Odysseus’ men shout out to Circe:

She came at once,

opened the shining doors, and asked them in.

So thinking nothing of it, in they went.

Eurylochus alone remained outside,

suspecting trickery. She led them in,

sat them on chairs, and blended them a potion

of barley, cheese, and golden honey, mixed

with Pramnian wine. She added potent drugs

to make them totally forget their home.

They took and drank the mixture. Then she struck them,

using her magic wand, and penned them in

the pigsty.

(10.229–240)

“Circe Changing Ulysses’ Men to Swine, (Ulyssis soci a Circe in porcos), from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphosis,’” Antonio Tempesta, etching, 1606, Rome.

After Eurylochus watches his fellow men turned to swine, he returns to the ship, overwhelmed with grief. He tells Odysseus of the plight of his men, and, against Eurylochus’s tearful pleading, Odysseus sets off alone to Circe’s palace. Along the way, the mercurial god Hermes (one of my favorite Greek gods) comes to his aid. Hermes gives Odysseus an herbal antidote to Circe’s poisoned wine and tells Odysseus what he must do to trick Circe and free his men. Hermes instructs Odysseus to sleep with Circe (after all, you cannot deny a goddess) but to first draw his sword and demand an oath from Circe to free his men and cause no further harm. Odysseus follows Hermes’ instructions

“Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses,” John William Waterhouse, oil painting, 1891, Gallery Oldham, England.

Circe is surprised when the magic wine does not change Odysseus; she is also intrigued. She says to Odysseus:

Who are you?

Where is your city? And who are your parents?

I am amazed that you could drink my potion

and yet not be bewitched. No other man

has drunk it and withstood the magic charm.

But you are different. Your mind is not

enchanted. You must be Odysseus,

the man who can adapt to anything.

Bright flashing Hermes of the golden wand

has often told me that you would sail here

from Troy in your swift ship. Now sheathe your sword

and come to bed with me. Through making love

we may begin to trust each other more.

(10.325–336)

Odysseus agrees to sleep with her, but demands she first fulfill her oath. Circe complies, promptly reversing the spell, changing Odysseus’ men from pigs back into human men, only taller, younger, and more handsome.

“Circe Restores Human Form to Odysseus’ Companions,” Giovanni Battista Trotti, fresco, c. 1610, Palazzo ducale del Giardino, Parma.

The men return to Circe’s hall unsettled and sobbing. Circe says to Odysseus:

“King,

clever Odysseus, Laertes’ son,

now stop encouraging this lamentation.

I know you and your men have suffered greatly,

out on the fish-filled sea, and on dry land

from hostile men. But it is time to eat

and drink some wine. You must get back the drive

you had when you set out from Ithaca.

You are worn down and brokenhearted, always

dwelling on pain and wandering. You never

feel joy at heart. You have endured too much.”

(10.455–465)

And so the “beautiful, dreadful goddess” becomes a compassionate and generous lover of Odysseus and host to him and his men. They stay with Circe for a year, and they are content. Odysseus relays:

We did as she had said. Then every day

for a whole year we feasted there on meat

and sweet strong wine.

(10.466–469)

“Circe enticing Ulysses,” Angelica Kauffmann, oil on canvas, 1786.

“Circe Preparing a Banquet for Ulysses,” Ludovico Pozzoserrato, 1605.

Homer does not describe this year-long hiatus on Circe’s island in detail. I managed to find another imagining of it, though, in Katherine Anne Porter’s beautiful, limited-edition book, A Defense of Circe, which was published in 1954. Porter expands upon this part of Circe’s story, adding details not found in The Odyssey:

The transformed warriors and the whole company, joined by still reluctant Eurylochus, stayed on cheerfully for a year as the guests of Circe. Odysseus shared her beautiful bed, in gentleness and candor, with that meeting in love and sleep and trust she had promised him.

– from A Defense of Circe, Katherine Anne Porter

After Odysseus and his crew’s year on her island, Odysseus asks Circe for help getting home to Ithaca. Circe gives Odysseus very specific guidance, instructing him to travel to Hades for advice from the blind prophet Tiresias. She later advises Odysseus on avoiding the dangers of the Sirens and the monster Scylla. Circe empowers Odysseus to make his way home alive (though, spoiler alert, he loses all his men on the journey).

The beauty of the story of Circe and her relationship with Odysseus, in my twenty-first-century mind, is that there is no diminishment of Circe’s power, wisdom, or independence. She and Odysseus become friends, lovers, and equals; she supports him and his men, and, when it is time, she lets him go.

The Sorceress, John William Waterhouse, oil on canvas, c. 1911 – 1915.

In this final painting, “The Sorceress,” by English artist John William Waterhouse, we see our beautiful Circe, once again with her book of magic and her (most likely) poisoned wine spilling out of the golden chalice. She appears pensive and sad, facing her feline companions across the table. Here, I think of Circe after Odysseus and his men have made their final departure from her island. She is an immortal goddess, and so, perhaps, she ponders a long life ahead without her mortal companion and lover, Odysseus, whom she loved more than any god.

I love this description of Circe and her “unique power” in Porter’s work:

She was one of the immortals, a daughter of Helios; on her mother’s side, granddaughter to the Almighty Ancient of Days, Oceanus. Of sunlight and sea water was her divine nature made, and her unique power as a goddess was that she could reveal to men the truth about themselves by showing to each man himself in his true shape according to his inmost nature. For this she was rightly dreaded and feared; her very name was a word of terror.

– from A Defense of Circe, Katherine Anne Porter

The primary sources which I have drawn from in my research and which I highly recommend are:

Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. Emily Wilson. New York, N.Y. : W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 2018.

Miller, Madeline. Circe. New York, N.Y.: Little Brown and Company, 2018.

Porter, Katherine Anne. A Defense of Circe. New York, N.Y.: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1954.

Yarnell, Judith. Transformations of Circe. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1994.