“Don’t Kiss Me I,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

In February, I enacted a performance and embodiment practice with early-twentieth-century French artist Claude Cahun. This practice resulted in a direct transmission from Claude to me through Luís Branco’s magic camera.

Luís and I shot hundreds of images on the French Riviera at La Napoule Art Foundation. In the studio and in and around the beautiful Chateau de la Napoule, we created a body of work in conversation with Claude Cahun and her lifelong photographic practice, much of which was produced with her partner in art and life, Marcel Moore.

Cahun (1894 – 1954), a surrealist intellectual, was a significant, multitalented artist. She was a performance artist, photographer, sculptor and writer. She was also a committed, even jailed, anti-Nazi activist. Cahun was gender ambiguous, a lesbian and a cross-dresser. (I use she/her pronouns for Cahun; the gender-neutral pronouns they/them, while perhaps more appropriate, were not in use during Cahun’s lifetime.) Cahun’s work, in both photography and writing, explores the many masks of selfhood. Cahun encourages us to examine the theater of identity, where we perform and inhabit roles that are imposed upon us as well as roles that we invent. Claude Cahun is my queer superheroine.

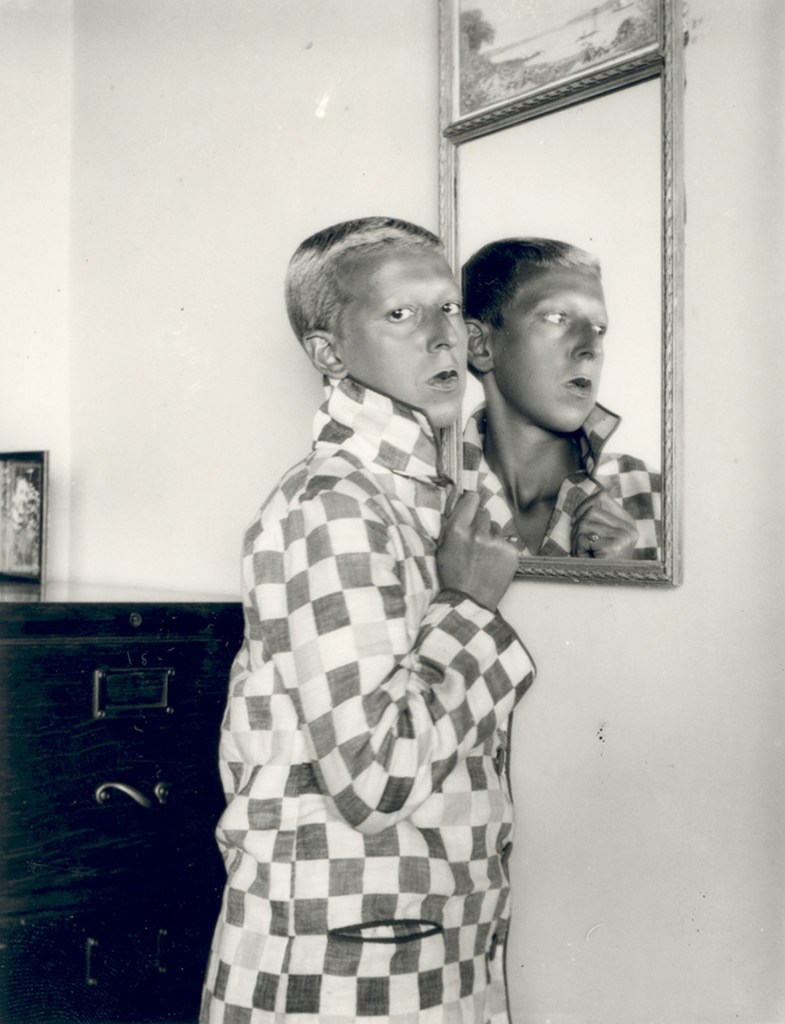

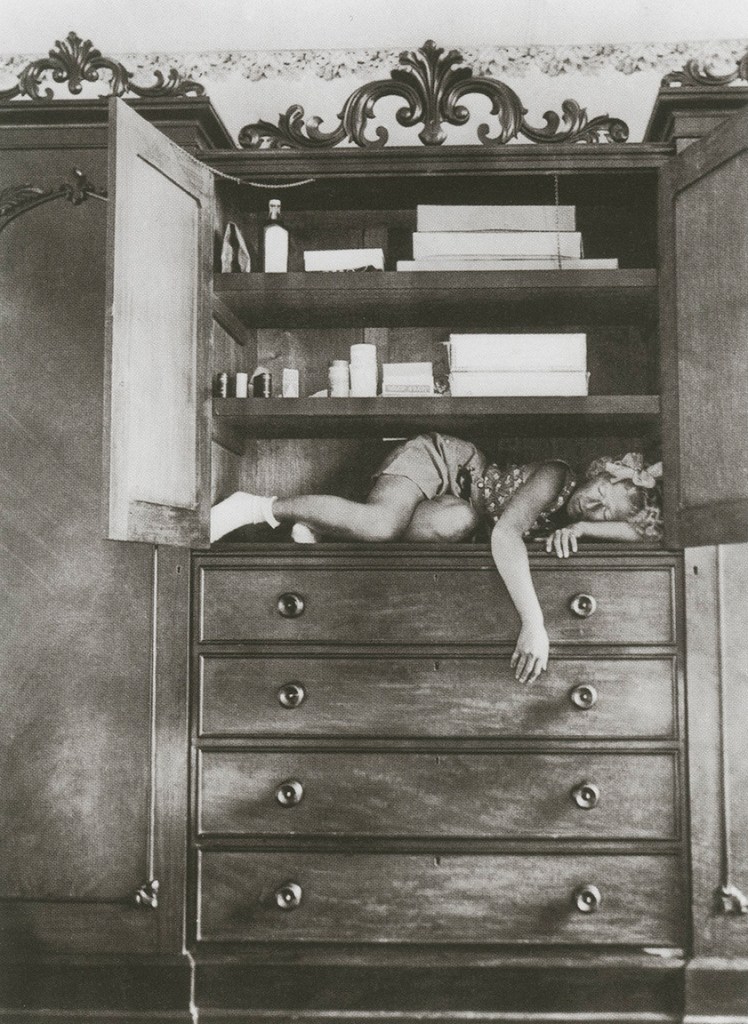

Untitled, Claude Cahun (with Marcel Moore), 1927.

The 1927 image of Cahun posing as a body builder (above) is one of my favorites in Cahun’s oeuvre. It plays on all sorts of tropes of identity and performance. The costume in the image is both masculine and feminine: the misplaced nipples and lips on the shirt, the delicate neck scarf and silk waist sash, the “I AM IN TRAINING DON’T KISS ME” message, the enormous dumbbell across her shoulders and the contrapposto stance that would never bear its weight. What is she in training for? The curlicue hair, the hearts on her cheeks and the dishtowels hung as a backdrop. It is all just plain funny and indicative of Cahun’s lifelong pursuit of “dressing up,” a pursuit she accomplished in her everyday life and in theater productions in Paris in the 1920s. For my enactments of this image, assemblage artist Jensina Endresen helped me create my own body-builder costume. My partner, Jamie, constructed the inflatable barbells that I brought with me to France. Et voilà!

“Don’t Kiss Me II,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

“Don’t Kiss Me III,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

On a more serious note…

The photograph above, of Cahun standing beside a mirror, is eerily striking. The mirror doubles her image—the “real” Cahun gazes toward the camera and us, while the mirror image of Cahun looks into the mirror itself and beyond. Cahun’s gaze is deadpan, serious. Her hair is shorn, very butch or masculine—hommasse in French. The jacket and the gesture are also masculine. Cahun was always toying with ideas of self-reflection, self-questioning and gender ambiguity.

“Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

– Claude Cahun, Disavowals, trans. Susan de Muth (Cambridge: MIT Press 2007), 151. Originally in Cahun’s Aveux non Avenus, 1930.

“I’ve been thinking about Claude Cahun I,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

In our triptych “I’ve been thinking about Claude Cahun,” Luís and I did not attempt a direct copy of Cahun’s photograph. Instead of gazing sidelong, as Cahun does, I gaze directly into the mirror. The three photographs depict the process of me “performing” my more butch, more masculine self. I cut my hair short (then later cut it off entirely). In all three images, the water and horizon of the Mediterranean are visible through the windows. I donned a Cahun-inspired checked jacket and a mask. The costume and the setting allude to an art-deco-era past or early Hollywood. I will be showing this triptych in a group exhibition called “Queer Perspectives” at Michael Warren Contemporary in Denver opening July 31st and up through August 30, 2025.

“I’ve been thinking about Claude Cahun II,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

“I’ve been thinking about Claude Cahun III,” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

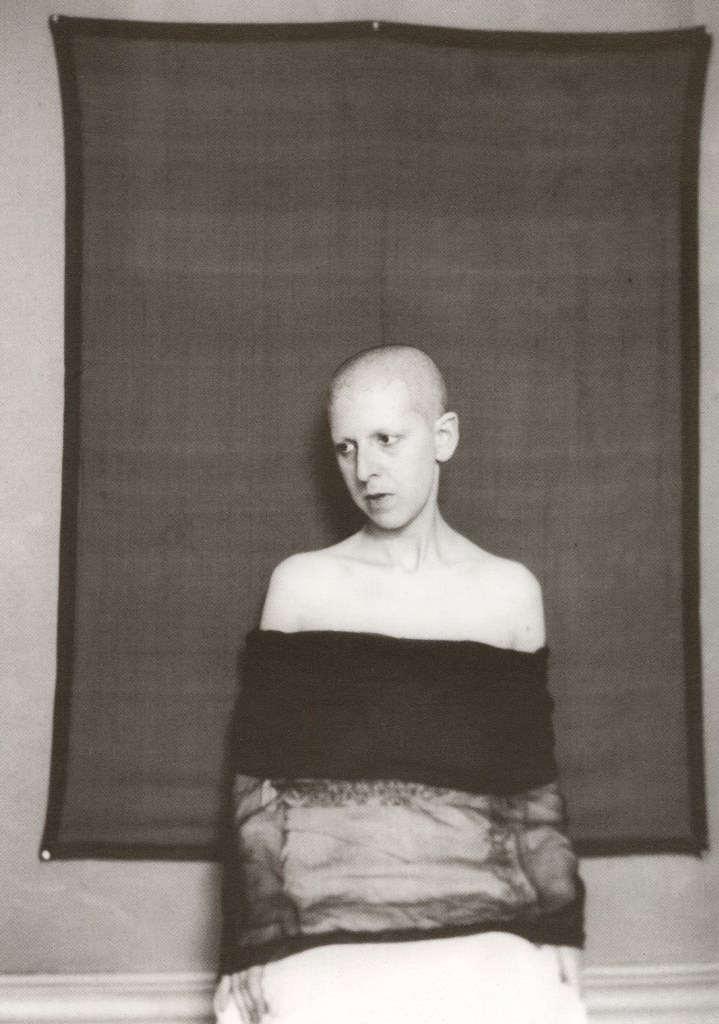

“Que me veux tu?” Claude Cahun (with Marcel Moore), 1929.

The double-headed image of Claude Cahun (above) is one of Cahun’s few titled photographs. “Que me veux tu?”, or “What do you want from me?”, speaks to Cahun’s never-ending existential struggle with and questioning of identity in her life and art

I had my head shaved at the beauty shop in La Napoule. It was kind of liberating. Luís shot a whole series of double exposures of this new hairless and quite androgynous “double me,” creating our own version of “What do you want from me?”

What do you want from me?” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

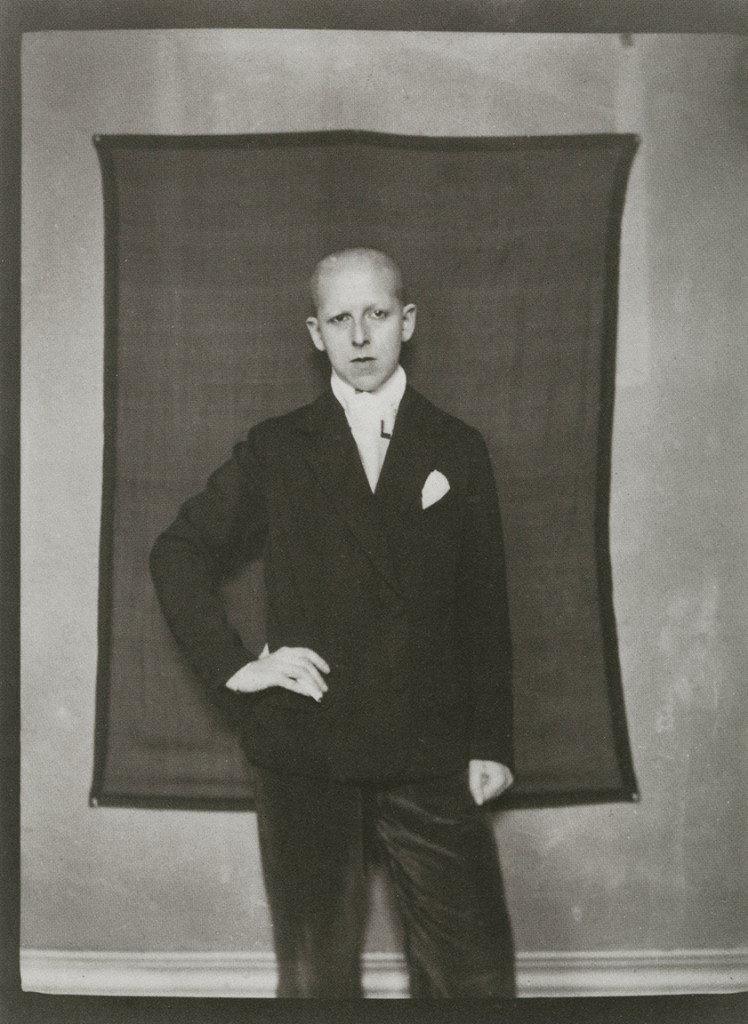

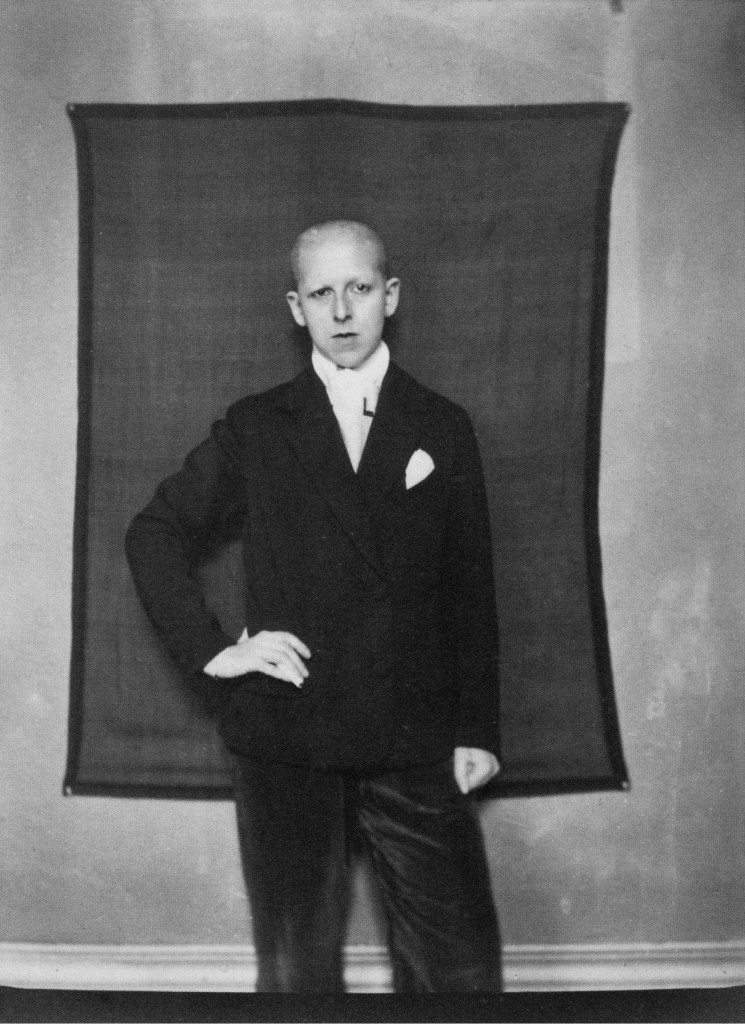

Untitled, Claude Cahun (with Marcel Moore), 1920.

Marcel Moore must have taken this image (above) of Claude in her dandy and gentleman-like attire in the early 1920s in Paris. They were living a life that allowed Cahun to explore her gender ambiguity in full.

“Masked (after Claude Cahun),” Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

As a Gentleman (after Claude Cahun), Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

Gilded, Sherry Wiggins and Luís Branco, 2025.

I received a transmission from Claude Cahun during this intense period in France. This last image, which I call “Gilded,” is one of my favorites. This was taken during our last photoshoot at La Napoule. I had applied gold makeup to my face. Cahun’s golden light shines through me.