Judith Beheading Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1611 – 1612, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

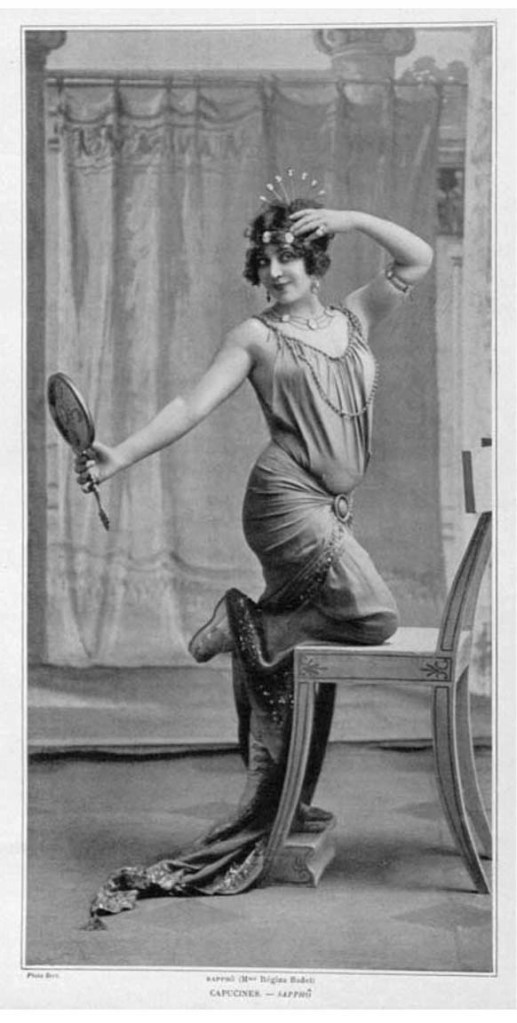

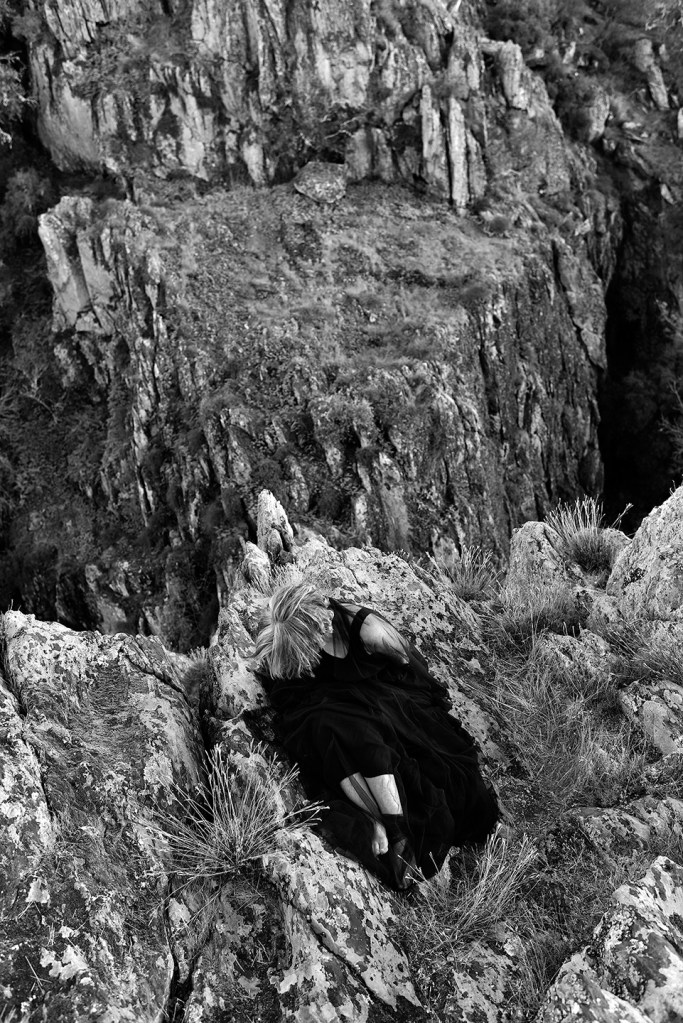

I am at the OBRAS Artist Residency in Renkum Holland preparing to embody and photograph my new but ancient heroines Judith and Sappho with my collaborator photographer Luis Branco. I am relooking at Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi’s (1593-1656) paintings of the ancient heroine Judith. Artemisia painted several portraits of Judith during her remarkable career as well as many other female heroines.

I have been studying the ancient fictional heroine Judith, who in the Book of Judith cut off the head of the (fictional) Assyrian general Holofernes. The Book of Judith is non historical fiction and can be seen as a theological novel or a religious parable (it is also considered to be a deuterocanonical book and/or apocrypha). It is not part of the Hebrew Bible, it’s canonicity in Christianity is complicated: however the story is well known in most Jewish and Christian religious traditions. The history of western art is filled with paintings of Judith— the Baroque painters particularly loved the gore and glamour of the story of Judith. You must recognize the magnificent painting by Caravaggio below that influenced Artemisia’s earliest paintings of Judith.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio, 1598 – 1599 or 1602, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

I have been reading The Book of Judith, in one version titled “Apocrypha Judith of the King James Bible 1611”. The original story was probably written sometime around the 2nd century BC. The story goes that Judith was a beautiful Jewish widow, told to be extremely virtuous and pious (the name Judith literally means woman from Judea). She lived near the fictional town of Bethulia ( supposedly near Jerusalelum). Judith spent her days praying in a tent on the roof of her house clothed in a widow’s poor sack cloth. The first chapters of the book tell of how the greedy (fictional) Assyrian king, Nebuchadnezzar, had sent his large army under the leadership of the general Holofernes to Palestine to conquer the Israelites. The Assyrian army camped in the valley near the town of Bethulia cutting off their water and food and ready to attack Bethulia and go on to take Jerusalem. The townspeople had no way of protecting themselves from the large army and they feared that their God would not save them. Our heroine Judith stepped into the situation and told the townspeople that they must not question God’s protection. Judith tells them that she will send prayers and messages to her/their God to “break down their (the Assyrian army) stateliness by the hand of a woman” to save the Jewish people. Judith made a plan which she did not reveal to the townspeople, and apparently God gave her the go ahead . . .

Then Judith took off her poor widow’s clothes and washed and anointed herself with precious ointments and dressed herself in her best garments:

“And she took sandals upon her feet, and put about her her bracelets, and her chains, and her rings, and her earrings, and all her ornaments, and decked herself bravely, to allure the eyes of all men that should see her.” {Apocrypha, Judith of the King James Bible 1611, 10:4}

And she went with her loyal maid Abra to the Assyrian camp (bringing with her wine and cheese and fine bread) and asked the soldiers to take her to their general Holofernes for she had a plan to help him to conquer the town of Bethulia. The soldiers were overwhelmed by her beauty and believed her words and led her to the tent of Holofernes who was also besot by her countenance and fooled by her words.

For several days and nights Judith acts to seduce and soften Holofernes, though she never takes to his bed . . . One night there is a feast in Holoferne’s tent and he gets very drunk and passes out on his bed. Holoferne’s servants and guards leave the tent and Judith takes this opportunity to cut off his head by her own hand with Holoferne’s sword. She smuggles the head out of the camp to Bethulia in the middle of the night aided by her maid Abra. When the townspeople see what Judith has accomplished they hang the head of Holofernes at the gate for all to see. They are amazed at what Judith has accomplished to save the Israelites and word goes out to all. The soldiers and servants of Holofernes discover the decapitated body in the tent and are horrified and afraid and quickly take up their horses and flee. As the Assyrian soldiers run away, the Israelites take their spoils. Judith is the savior of Israel and a heroine forever more. I won’t get into the religious, political, historical, patriarchal and feminist implications of this story—there are many ways to interpret this story. I am not Christian or Jewish, I am a Feminist and I do love this story of Judith’s intelligent maneuvering, her courage and her careful execution of her plan. The the jewelry, the fine clothes, the food, the seduction, the sword: what’s not to love?

Judith and Her Maidservant, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1613 – 1614, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

There are many paintings by many painters depicting Judith decapitating Holofernes and the aftermath. The several paintings that Artemisia Gentileschi painted of Judith over a period of 30 years always show Judith with her loyal maid servant Abra. As in many of Artemisia’s paintings, she often inserted her own visage in the place of the heroine and here she might insert herself as both Judith and Abra. All of these paintings captivate me! The story of Judith was most certainly originally written by a man. Artemisia’s viewpoint is, of course, reflective of a woman’s experience and perhaps even of Artemisia’s own experience negotiating and manipulating her career and life in a 17th century man’s world. Artemisia was most certainly a feminist as well as an incredibly productive and remarkable artist. She had suffered sexual violence, herself, at a young age by the older painter Augustino Tassi, who was a friend of her father the painter Orazio Gentileschi. Tassi was put to trial for the act but never really suffered any repercussions, while Artemisia suffered many consequences. Artemisia was a 17th century “me too” woman who managed to live a productive and creative life, though there is often a subtle element of violence in her paintings and there is most certainly an intense subjectivity that is not often seen in the paintings by men. Below is my personal favorite of Artemisia Gentileschi’s paintings of Judith.

Judith and her Maidservant, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1625, Detroit Institute of the Arts

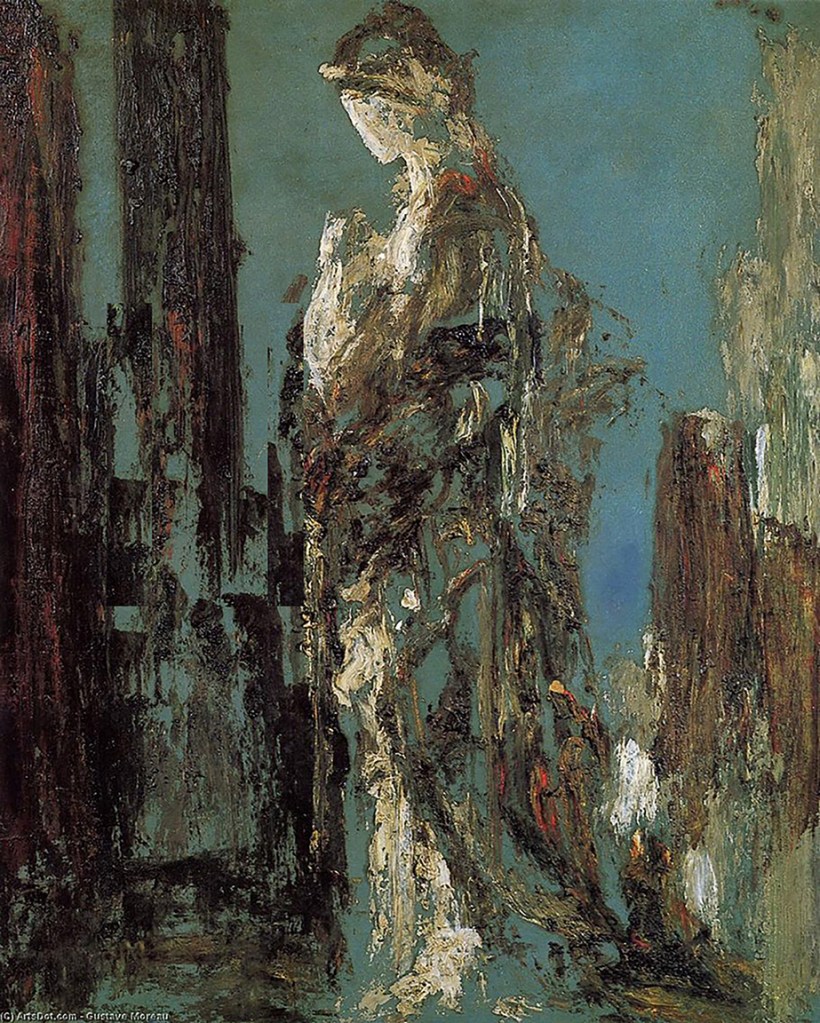

A few of my favorite Judiths’ by men . . .

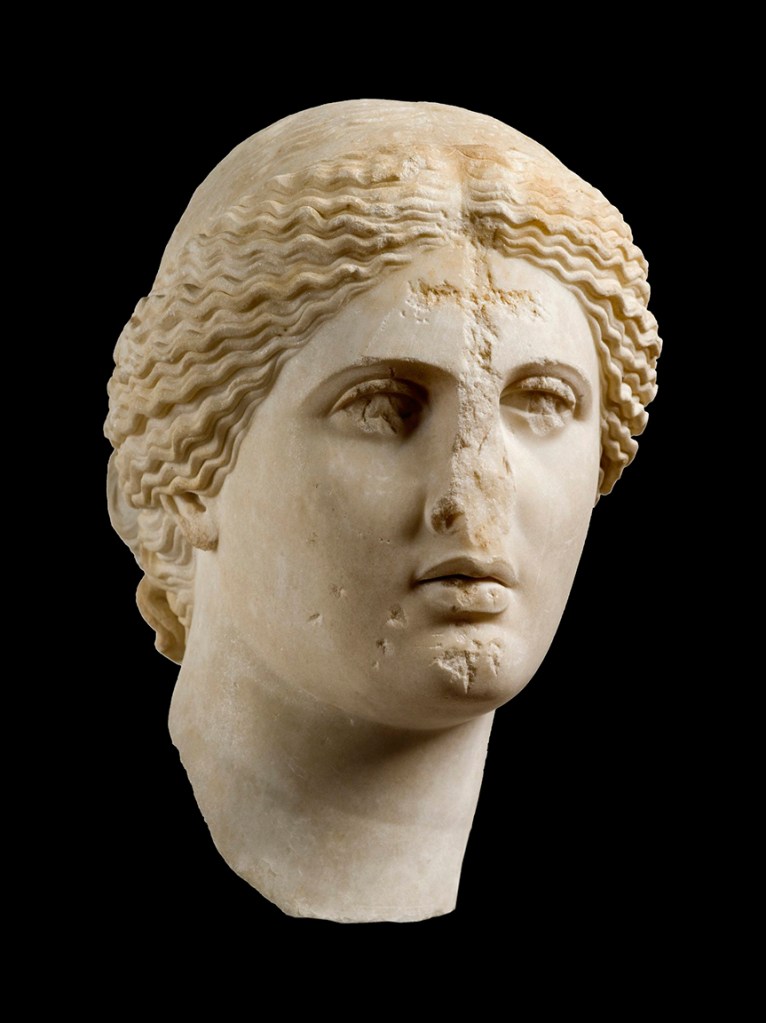

Judith, Giorgione, 1504, Hermitage, Saint Petersburg

Judith with the Head of Holofernes, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530, The Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Judith with the Head of Holofernes, Jan Massey, 1543, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

and some more contemporary performances of Judith . . .

Martha Graham Dance Company performing Judith, with Peggy Lyman, 1980

And I love this performance of Judith by Martine Guitierrez (from their Icon series made for bus stations in NYC), 2021

And finally one more by Artemisia—this last painting below was only recently found. A younger Judith (and an older Abra) look out of the frame, the head of Holofernes in the center of the painting. This is one of Gentileschi’s later paintings of Judith.

Judith and Her Maidservant and the Head of Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1639 or 1640, Nasjonal Museet, Oslo

I have many ideas and a sword to be wielded as I prepare to perform Judith (and also Sappho)! This blog post was written with some haste, please forgive the writing. I am working in Holland until the 27th of October.