If I vibrate with vibrations other than yours, must you conclude that my flesh is insensitive? – Claude Cahun from the essay ‘Salome the Skeptic’ (note 1)

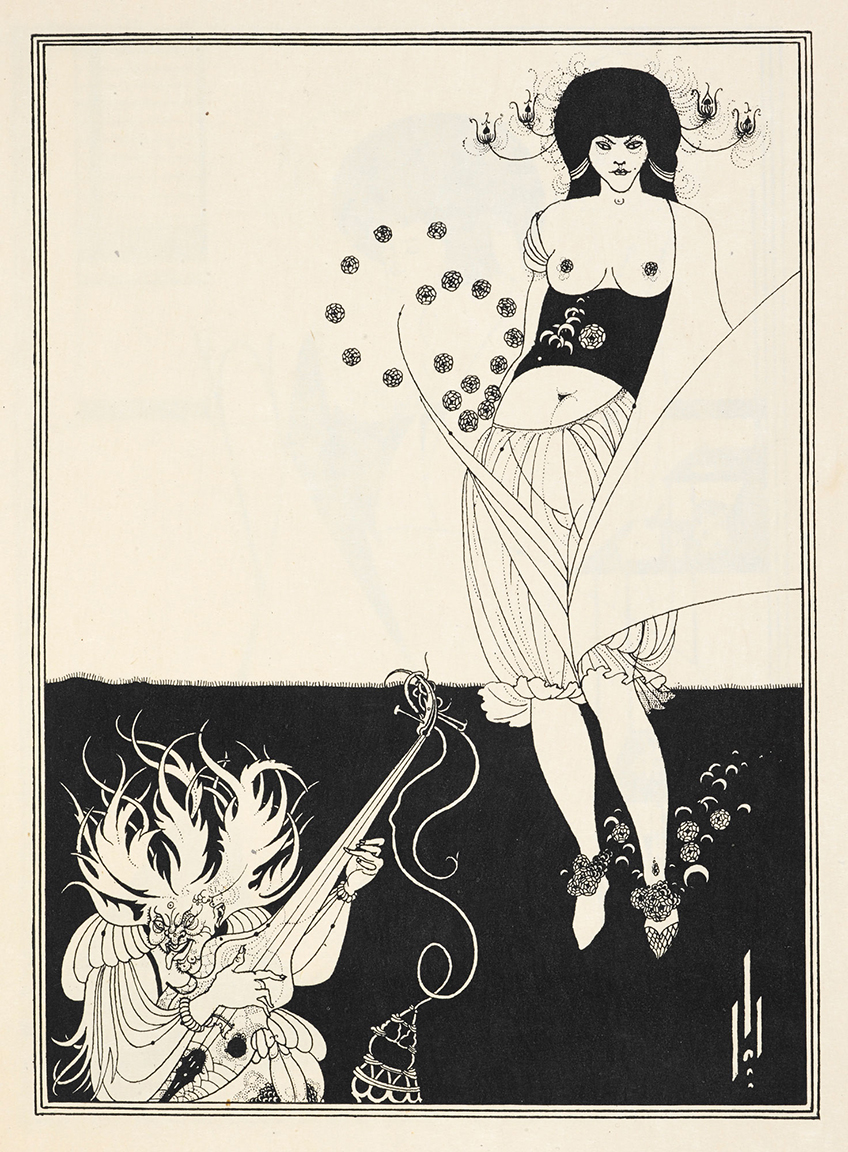

Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax. 1893. One of Beardsley’s sixteen drawings for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome.

I am beginning a project with my new heroine Salome – based on fabulous French feminist artist Claude Cahun’s essay ‘Salome the Skeptic’ in her book of essays titled Heroines. Cahun published the book in 1925. The fifteen essays in her book question and reconstruct the representations of some of our most famous heroines – from the bible, antiquity, fairy tales and from popular culture. Cahun’s essay in Heroines, ‘Salome the Skeptic,’ is odd and a little hard to understand, and also fascinating if you try to engage with it. The thing I love about Claude Cahun is that she pushes me to do my own research and examination of history, of art and of our heroines and how they have been performed and personified.

Salome has been represented over two millenniums as a historical figure, a biblical persona and as a mythical and fantastical creature and woman. She has been portrayed extensively in paintings, in literature and in the late 19th century and early 20th century in theatre, opera and dance and ultimately film. Salome is a fascinating character and she, of course, has been primarily portrayed by men. Many of these depictions of Salome are (as in the New Testament) portraits of the young Judean princess who danced for her stepfather Herod Antipas and in return asked for the head of John the Baptist (on a silver platter). Whether she acts to appease her vengeful mother Herodias or as the story morphs through time, because she is actually in love with the prophet and spurned by him, Salome’s persona becomes by the 19th century a portrait of a femme fatale, a wanton, lustful, seductive creature and a stereotyped and “orientalized” woman to boot.

Titian, Salome, 1515

Carravaggio, Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, 1609

Henri Regnault, Salome, 1870

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876

Cahun addresses her essay ‘Salome the Skeptic’ “for O.W.” (for Oscar Wilde). Cahun was an ardent admirer of the infamous Irish poet, writer, playwright Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). They were both brilliant artists and intellectuals with homosexual and bi-sexual tendencies and to greater and lesser degrees they were both ostracized for their queer proclivities. Cahun never reached the level of notoriety of Wilde. In 1891 Oscar Wilde wrote the (then and for many years after) controversial play Salomé in French, it was translated into English in 1893. The play, in its book form, was illustrated (also scandalously) by the young Aubrey Beardsley (1872 – 1898) with these , erotic, gender bending, Japanese inspired black and white ink drawings that were first published in 1894. The play (and the drawings) were severe rebukes to Victorian repressive views of women, sexuality, gender and to some degree homosexuality. Wilde mentions “the dance of the seven veils” that Salome is to perform in the play (without any direction or choreography). The play, the illustrations, Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley were seen as transgressive – the eroticism, the biblical references, the murder story, Salome’s kissing the head of Jokanaan (John the Baptist), were all shocking at the time. The play was not produced in England for years and was first performed in Paris in 1896. Wilde never saw the play produced as he was put in jail for sodomy and “gross indecency” from 1895 to 1897 and died in 1900. He spent the last three years of his life impoverished and in ill health and and died of meningitus at 46 years old. Beardsley also died young at 26 in 1898 of tuberculosis. However, they seemingly set off a firestorm of representations of Salome.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Stomach Dance, 1893. Another of Beardsley’s sixteen drawings for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Dancer’s Reward, 1893. Another of Beardsley’s sixteen drawings for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome.

In 1906 Richard Strauss created the opera Salome based on Wilde’s play, with a “dance of the seven veils” as a main feature– this opera continues to be performed to this day. Wilde’s play inspired a form of “Salomania” at the beginning of the 20th century where many women performers put on acts inspired by Salome’s “erotic” dance. This dance of Salome was ultimately performed in the nude (as well as in scant clothing) by several renowned actresses and is sometimes considered the origin of the “strip tease.” Maude Allan, Mata Hari, Ida Rubinstein, and eventually Rita Hayworth and many other actresses have performed as Salome. In the last decade Al Pacino became obsessed with the play and with Wilde – Pacino acts in the play, and produces and acts in a documentary and a film with Jessica Chastain as Salome and Pacino as the lustful Herod. The stories, the paintings, the literature, Oscar Wilde’s play, the films and these women performers and Salome herself can all be viewed within contradictory frameworks of contemporary feminism and gender politics. Are the performers empowered women dancing with and displaying their bodies as sexual beings with agency and artfulness? Or does the “male gaze” upon these beautiful dancers and performers somehow disempower them? Is the self-stripping down of the female body, the “unveiling” an act of freedom or an act of acquiescence to male power and dominance?

According to what I have read, Wilde is one of the first to mention “the dance of the seven veils” in literature (or anywhere for that matter). Some scholars think that Wilde’s intention was more esoteric then erotic, and that the unveiling of the soul was inherent in this action/dance. The unveiling dance has also been linked to the Mesopotamian goddess Innana’s ( and also Ishtar’s) descent to the underworld and her return through the “seven gates.” In this epic tale the ancient goddess “lets go” of a garment or a jewel or an element of power at each gate, eventually arriving in the underworld naked and unadorned. Wilde (and Cahun) were both classically educated and must have known this ancient myth as well.

All these stories and representations of Salome have transfixed me. I am seduced by this femme fatale heroine in all her various incarnations. I am considering how I might “embody” Salome in performative photographs myself. The 64 year old Salome might be quite strange, we will see… Following are more of the myriad representations of Salome I have found – starting with the Salome fetish at the beginning of the 20th century through Al Pacino’s 21st century obsession with O.W. and Salome.

Dutch actress, dancer, courtesan and spy Mata Hari as Salome, 1906

Canadian actress Maude Allan as Salome, 1908

Maud Allan as Salome, 1908

Russian actress, ballerina, art patron Ida Rubinstein as Salome, date?

Russian American actress and producer Alla Nazimova’s film production of Salome, 1922

American actress Rita Hayworth as Salome in the film Salome, 1953

American actress Jessica Chastain as Salome in Al Pacino’s film Wilde Salomé, 2011

and I end with one of Beardsley’s more haunting images:

Aubrey Beardsley, The Woman in the Moon, 1893. Another of Beardsley’s sixteen drawings for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome.

“How strange they are, people who believe that it has happened. How can they? One thing only in life, the dream, seems to me beautiful enough, moving enough, to merit your becoming so disturbed that you have to laugh or cry.” – Claude Cahun from the essay ‘Salome the Skeptic’ (note 2)

Notes 1 and 2: I am quoting Cahun from Norman MacAfee’s English translation of Cahun’s text. Cahun, Claude (translated by Norman MacAfee 1998). ‘Heroines – Salome the Skeptic,’ in Rice, Shelley (ed.) Inverted Odysseys. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, pp. 76-79, 1999.

Terrific Sherry! Suzie

LikeLike

Thank you, lots of research! xo Sherry

LikeLike